Benedictine Farm was created with reverence to the monastic gardens and landscapes of the Benedictines from the 5th to 16th centuries with the overall subject matter being that of the Pastoral Genre. The curated environment encompasses 40 acres in rural Worthington, Pennsylvania. On three acres of land, a number of gardens have been replicated based on 16th c. designs and philosophies on the natural world including, a Herbularius (medicinal herb garden), Hortus (Vegetable garden), Flowering beds, and a Hortus Conclusus (Enclosed Garden). Among the acreage, (locus amoenus), paths have been cut for contemplative walks, eventually reaching a patch of wood at the top of the land. At the base of the gardens, sits and acre pond to catch fish from. Period correct Heritage breed chickens free range the honey bee meadow providing high quality eggs.

The construction of the gardens and the chosen genus of herbs, vegetables, and flowers have been informed by in depth research of monastic records, herbals, and manuscripts of the European Middle Ages. Literature, paintings, poetry and travels to European historical sites , visited by founder, Cassandra have also been utilized.

With a comprehensive range of medicinal plants, herbs, and flowers grown with organic practices, Benedictine Farms prepares Tisanes blended with monastic concepts of healing. We also offer honey, and a full range of historical herbs and flowers grown in our greenhouse. Open for visitation for those interested in beauty and horticultural history; experiencing how the Benedictine monasteries, natural landscapes, gardens, the arts, literature and bucolic lifestyle informed one another throughout centuries until present day.

As Benedictine Farm continues to grow, we will embrace multiple facets of “the Arts” pertaining to the Benedictines and Pastoral Genre, i.e immersive events, lectures, and performances. Skill based workshops will be taught by artisans that are experienced in traditional crafts that proved to sustain the self sufficient life style of both the monasteries and country life.

~

APOLOGIA> In this description, I attempt to give an condensed overview; a history of the Pastoral in literature and the Arts. The eras of this genre can be traced back to 3rd c BC and reach the dawn of the Romantic period. With this being said, most books I have read on the topic are in numerous volumes laid over 1000+ pages. This is an exceptionally edited vignette to give the reader a sense of the topic throughout the centuries. Secondly, my aim is to explain why and how the Benedictine Monasteries are not merely related, but played a crucial cultural and intellectual role in the fate of the Pastoral genre.

KEY TERMS

Arcadia (Greek: ApKádia): a region in Greece located the in the central finger of Peloponnese. In Ancient Greece, its fascination lay in the remote distance from the city of Athens. Regarded as a bucolic setting where cave dwelling shepherds and their God of nature Pan resided. In later terminology; a physical and metaphysical place of the locus amoenus in the Pastoral tradition.

Pastoral (Latin: pastor>shepherd) works of literature pertaining to a sometimes idealized version of the countryside. Themes of shepherds, shepherdess, country dwelling poets in remote wooded landscapes, solitude, unrequited love and the corruption of city life are utilized.

Idyll (Greek:eidos>picture) The most idealized form in Pastoral literature; an extremely happy or peaceful picturesque scene usually unsustainable.

Bucolic (Greek:boukolos>herdsman) a more realistic form of poetry in the pastoral mode with a focus on animals.

Locus Amoenus translates from Latin to “pleasant place” used by modern scholars to refer to an idyllic landscape in painting or literary terms typically involving trees, shade, meadows and running waters and song birds.

Eclogue a short pastoral poem

Georgic (Greek: geōrgos>farmer) a poem or book dealing with agricultural or rural topics; specifically on the toil in opposition to the more leisurely qualities of the Idyll.

Pastourelle Medieval (old) French lyric form and poetic genre that originated in the 12th c and flourished through the 13th. It typically presents a dialogue between a knight and a shepherdess; romantic overtones in a rural setting exploring emotions of love in shepherds and shepherdess.

What is Pastoral?

Pastoral art, poetry and literature principally offer a conventionalized picture of rural life, the naturalness and innocence which is contrasted favorably to the corruption and artificialities of city life and the court. It deals with tensions between nature and art, the real and the ideal, the actual and the mythical. Although pastoral works have been written from the point of view of a shepherd they were often penned by sophisticated urban poets. It represents a continual longing for a non existent Golden Age in idyllic landscape or garden settings, using the simple image of the shepherd to represent complex, often social and political issues. Its origins can be traced back to the 3rd c BC.

The Temptest, Giorgione c. 1506

Classical Origins

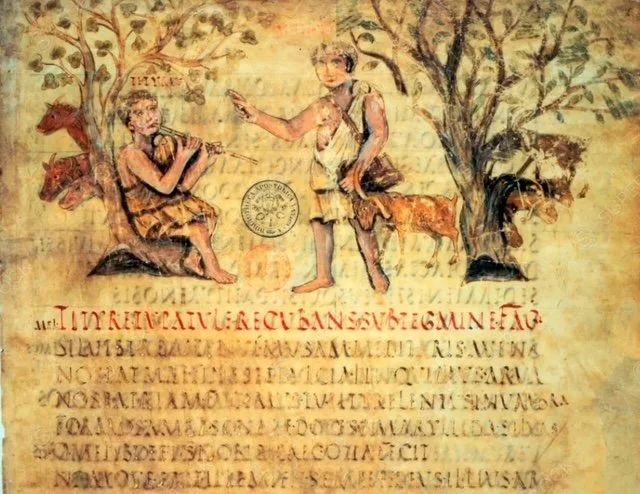

In ancient times, Arkadia was a mountainous region in Greece. Its fascination lay in its remoteness from the city of Athens. Personifying this nostalgic, dream like countryside was the deity Pan, where himself and fellow Arcadians dwelt in caves, famously documented by Homer in his Hymn to Pan. Not unlike Homer and his position towards Athens, was Sicilian born poet Theocritus. His Idylls written in the 3rd c BC, poems also known as Boukolika, “ox herding poems” were written for the enjoyment of an educated newly urban audience due to the development of Alexandria. The creation of this city marks the first time people felt trapped by their truly urbanized surroundings. The herdsmen in Theocritus’ poetry carry with them a sense of the past and its loss embodied in the story of, Daphnis. His ‘bucolic’ poetry differed in many ways from what followed and ‘pastoral’ really evolved from imitations and readings of Theocritus’ greatest imitator, Virgil. For Theocritus’, his poems may be better understood against the background of Hellenistic poetry, where bucolic terminology suggest the exchange of song. The poet wants his audience to think of real or believed traditions of Sicilian bucolic song making. Real shepherds and goatherds did fill the long watching hours with music and song, and this had always been part of how such ‘simple people’ were imagined in art. He is credited for the first piece of literature in which all others in the the Pastoral realm are bound.

Flute carved from a sheep’s tibia. Found in the Cotswolds, similar to the one found at Keynshams Abbey dated 14th c image Cotswolds Archeology

Virgil, The Development of Pastoral in the Greco Roman World

The idylls of Theocritus may have remained obscure Greek verse if it had not been for Virgil who brought the Pastoral to its most enduring form. For it was his works that were the first point of reference from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. In this early modern period, virtually anyone that could read was familiar with them. Virgil did not take from Theocritus but built upon the foundation of the genre with his words, embedded in his personal experience. As stated in the previous paragraph, Pastoral is embedded in a song. The song is necessarily played, sung, spoken, felt in the landscape but, in Virgil’s work, the landscape listens to the pastoral’s music- specifically a woodland landscape, removed from the rest of society.

Virgil (70-90 BC) was born into a family of modest landowners. The family farm was in the most fertile region of Italy of the time, modern day Pietole. As a child, Virgil was able to wander freely in his diverse family estate taking a keen interest in both farming practices and the natural world. Civil war broke out in his country at the hand of Julius Caesar, the rich land of his father was confiscated by Augustus and dived into 60 allotments for resettlement. He never returned. These events greatly affected Virgil, leaving a strong influence on his writing and longing for an escape from chaos and violence and a nostalgia for peace of an Arcadian landscape.

In his later years, while in Naples, Virgil was part of a philosophical circle known as “The Garden” which focused on Epicureanism; a belief that obtaining the greatest good was through living modestly and gaining knowledge of the workings of the world. Epicureans were regarded as antisocial , even revolutionary and had a growing sense of resentment towards authority. This stood in opposition to the more popular Stoics beliefs and support of the Roman Republic. The political complexity implicit in poems but never fully explained, offered Virgil the possibility of addressing complicated and dangerous material without making his own position explicit.

In essence, the pastoral presents the reader with a contrast between idyllic harmony of an alternative world, in which man lives in unity with nature, and the reality which threatens to destroy it. The reader is both seeing it and losing it at the same time. This is the continuing fascination of the pastoral which has afforded generations of artists and writers the ability to express their displacement whilst hiding behind the guise of pastoral.

Virgil’s long poem. Georgics (Greek ‘to farm’) was more of an observation of farm management he saw as a child in contrast to the more dream like state of the Eclogues. His childhood experiences left him with a passionate love of the countryside. He had come to see the small farmer as a metaphor for all that was good in the nation. The unfortunate reality was that in the aftermath of the Civil War, small farmers deserted the countryside leaving the land to be managed by absentee landlords who resided in Rome. (almost 2000 years later during the Enlightenment in 1770 Oliver Goldsmith writes Deserted Village, a pastoral mourning the decline of rural life in England) The result was the an inevitable decline in the farming landscape and the state of the countryside was a matter of great concern to Virgil. Though the Georgics appear to be a treatise on farming, they are directed at the Imperial circle in Rome. Virgil wanted to restore a sense of pride in the work of the farmer. He argued that the true Italian way of life, when things were better, had been an agricultural one. Virgil’s message went further than reaching absentee landlords to the restoration of a way of life. Just as he had created the powerful image of Arcadia in the Eclogues, so in the Georgics he set out a powerful vision of the farmer as part of the organic whole, dignified and beautiful in close accord with nature. To establish ancient credentials, Virgil used the works of Greek writer Hesiod, a small farmer from Northern Greece who wrote two pomes: Works and Days and Theogony. The first was a sort of handbook for farmers and the other, and explanation of nature and the history of Gods. 1

...the father of agriculture

Gave us a hard calling, he first decreed it an art

To work the fields, sent worries to sharpen our moral wits

and would not allow his realm to grow listless from lethargy.

Virgil: Georgics I, 123-7

One of the constant themes was the value of hard work. Above Virgil takes up Hesiod’s lines that the farmer should observe justice and piety as well as follow the rhythms of hard work.

One governing thought that Greek philosophers held, revisited throughout this explanation is the idea of mans powerful progress from primitive ignorance to civilized power, and the ancient association between the culture of the land and the culture of the mind. Virgil’s idealizing of of the countryside, country values and the poets capacity to describe the landscape was a key factor in the later development of pastoral poetry. (e.g Petrarch’s Secret c.1350s)

Manuscript of Virgil’s Georgics, Vatican City Library

Christendom

.....Now is the last age of the Cumaean prophecy: the great cycle of centuries is born anew. Now Virgin Justice returns, and Saturn’s reign. Now a new race descends from the heavens above. Only favor the boy, who born pure, the iron race shall begin to cease and the golden to arise over the all the world. Rise up through the world, now your Apollo reigns.

Virgil’s Eclogues lines 4-13

‘He shall receive the life of gods, and see the gods, mixing with heros, and he himself be seen by them, And shall rule a world made peaceful by his father’s virtues.

lines 15-30

The serpent shall perish, and the deceitful poison plant shall perish; Assyrian spices shall spring up everywhere.

Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue is also referred to as The Messianic Eclogue. Virgil speaks of the birth of a miraculous child who will usher in a ‘new golden age’ of peace, prosperity and justice. The poet draws on prophecies of Cumaean Sibyl, (a Greek prophetess who is even featured on Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling as a witness to Divine Truth) and themes of cosmic renewal.

The coming of a child born pure, renewing the cosmos mirrors the language and content of Old testament prophet, Isaiah. The poem also describes an end to the iron age,(time of war and corruption) and the serpent perishing. To Christians, this echoed the Genesis promise that the serpent would be crushed by the woman’s seed (Genesis 3:15) another Messianic prophecy.

The early Christian Fathers saw Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue as a pagan foreshadowing of the birth of Christ; that God’s truth was not limited to the Jews but that the pagans had a glimpse of Divine revelation and prophecy as well.

Between 250-420 BC Saint Augustine, Saint Jerome, Eusebius of Caesarea and Lactantius all reference and comment on Virgil’s foreshadowing as a supporting detail in the case that pre Christians were unknowingly being prepared and inspired by Christ. It goes without being said that this is an ambiguous description of Christ’s birth and is an ongoing debate between theologians and literary scholars.

Virgil was the most revered poet in Roman Literature. The cultural prestige of showing that he prophesied the coming of Christ, was hugely beneficial in legitimizing Christianity in a Greco-Roman world. His pastoral style as a whole was rooted and woven into the surrounding landscape. In the following section I highlight the ways in which the Christian tradition is a kin to these perennial themes unbound by the construct of time.